Some of the LAVA Herstory

by Tighe Instone

When the British Parliament (which Aotearoa/NZ followed) attempted, in 1921, to make lesbian sexual activities punishable under the law, Lieutenant Moore-Brabazon suggested there were three ways of dealing with lesbians: 1) The death penalty would stamp them out. 2) Locking them up like lunatics would get rid of them. 3) Ignore them, not notice them, not advertise them, and prevent “…harm by introducing into the minds of perfectly innocent people the most revolting thoughts”. Hence - the law was not amended.

Lesbian Action for Visibility in Aotearoa (LAVA) was formed in December 1988 to bring to public attention examples of discrimination against lesbians and ways in which these could be countered. Denial of basic human rights (i.e. the right to work, have access to goods and services and to public places), aggressive actions against lesbians and the maintenance of lesbian invisibility were identified as examples of discrimination.

The Homosexual Law Reform Bill (HLRB), decriminalizing homosexual acts between consenting males over the age of sixteen years, was a private member’s bill sponsored by Fran Wilde and had been passed by the New Zealand Parliament in July 1986. Part Two of the HLRB Bill would have provided protection from discrimination for homosexuals under the Human Rights Act - but it was defeated. LAVA was formed when Wellington lesbians became aware the Labour Government was planning to introduce another bill that, if it were passed, would give homosexuals and people with HIV/AIDS protection from discrimination under Human Rights Act.

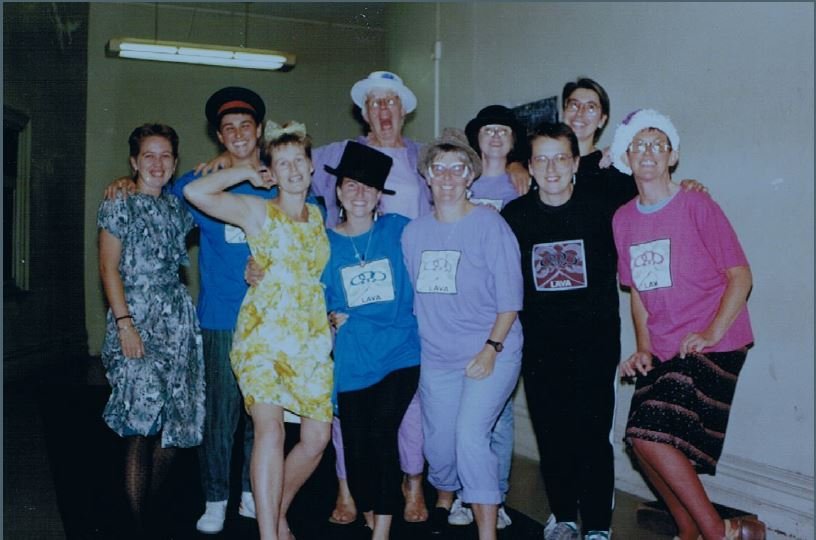

LAVA set about organizing a lesbian visibility campaign and support for the proposed legislation – but with reservations about the wording. Nina Zimowit designed the motifs for the LAVA t-shirts and when no lesbian entertainers were available to perform at the Lesbian and Gay Fair the LAVA singers came into being and filled the gap!

The LAVA Singers

On the last Parliamentary sitting day before the 1990 election the Labour Government introduced the Human Rights Amendment Bill. LAVA supported the principle that legislation was required to prevent discrimination where prejudice and disempowerment existed but opposed the inclusion of lesbians under the umbrella term “homosexual”. LAVA argued that, while the dictionary definition of homosexual includes both male and female, in general use the term tended to refer just to males. By including lesbians in this way the proposed legislation would simply maintain lesbian invisibility and the legislation would be discriminatory in itself.

Some gay men opposed LAVA’s position – they said it was genocidal and informed the Collective that the Minister of Justice, Geoffrey Palmer, was convinced that if the word lesbian was included in the Bill it would be defeated and the lives of many people with HIV/AIDS would be lost. Nevertheless the group “People With AIDS” (which later became “Body Positive”) was supportive of LAVA.

LAVA also opposed the use of the term “sexual orientation” and the inclusion of “heterosexuals” arguing that sexual orientation was far too broad a term and that heterosexuals do not require protection. LAVA pointed out that discrimination could only occur where there was prejudice and power. It was the power behind the institutionalization of heterosexuality that created the need for protection from discrimination for lesbians and gay men.

The National Party won the 1990 election and the new Government dispensed with Labour’s Bill and introduced The Human Rights Bill and Katherine O’Regan’s Supplementary Order Paper 182 (SOP 182). The submissions that had been received in response to Labour’s Bill were to be carried over and considered with the new Bill.

Katherine O’Regan’s SOP 182 amended National’s Bill by adding to the grounds of disability “(vi) the presence in the body of organisms capable of causing illness” and the ground “(m) Sexual orientation, which means a heterosexual, homosexual or bi-sexual orientation”. The National Government was not prepared to include protection for homosexuals and people with HIV/AIDS in the Government Bill - hence the need for SOP 182.

LAVA formed a Canterbury Branch which, together with Wellington lesbians lobbied Katherine O’Regan re the wording. She happily amended the SOP 182 so that it read “(m) Sexual orientation, which means a heterosexual, lesbian, homosexual or bi-sexual orientation.” The Bill was passed and became law in February 1994.

In July of the same year, New York celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots. The celebrations were preceded by the biggest ever Gay Games (15,000 athletes competed) a cultural festival, the International Lesbian and Gay Association Annual Conference plus many other conferences and PRIDE activities – not just in New York but all over the USA. 1.1 million LGBTQ people from all over the USA and different parts of the world attended. There was a march through New York city to Central Park where a huge rally took place.

At the rally, the Topp Twins sang and Ngahuia Te Awekotuku addressed the 1.1 million LGBTQ crowd wearing her LAVA t-shirt.

Ngahuia said later that when she spoke to that one million plus crowd it was a “magical, strange, terrifying, unforgettable moment”. It was herstory in the making and Ngahuia’s strong, stirring address was extremely well received by the enormous crowd. LAVA and Lesbian Radio Otautahi/Christchurch had endorsed Wellington Lesbian Radio’s nomination of Ngahuia as a speaker to represent the South Pacific. The letter of endorsement said “Ngahuia is an indigenous woman who was refused entry to the USA having won a scholarship to study there. This entry permit refusal was on the grounds that she was a ‘sexual deviant’. Ngahuia was a founder of Gay Liberation in this country and her commitment to Lesbian and Gay Politics has endured over a quarter of a century. As a speaker, Ngahuia is inspirational and we believe that her contribution to Stonewall 25 would be an interesting and constructive one. Her ability to bring his/herstory alive to those who follow her will be an inspiration to Lesbians and Gay men. Ngahuia is a lesbian who would be able to reach a million people and she imparts her mana, her wairua, her wisdom and her knowledge”.

Also during 1994 LAVA, in Canterbury, received funding from the Lotteries Commission to produce a Lesbian Newsletter. Viv Jones designed the cover and the first issue appealed to readers to enter a competition to name the newsletter. It became the Otautahi Lesbian Outpost (OLO).

The cover of the first issue of OLO, designed by Viv Jones.

Early on OLO was asked to publish an advertisement for a lesbian support group, submitted by a m-f transsexual who identified as a lesbian. The advertisement did not state that the advertiser was a m-f transsexual. The legal adviser at the Auckland Human Rights Commission Office (HRC) told OLO that if a person identified as a lesbian then under the Human Rights Act (HRA) they were a lesbian. OLO challenged this statement on the grounds that although the HRA does not define lesbian the Oxford and Collins Dictionaries say a lesbian is a “homosexual woman” and that a woman is “human female”. A transsexual was not a female and therefore could not be a lesbian. OLO also pointed out that anyone could identify as a Human Rights Commissioner – but that would not mean they were one. Subsequently the HRC advised OLO that under the HRA the collective could refuse to publish the advertisement of a m-f transsexual on the grounds that biologically he was a man. In the October 1994 issue of OLO readers were informed of these facts and were assured that the OLO Collective absolutely supported the right of transsexual people to have protection under the HRA but reserved the right of lesbians to lesbian only resources and spaces. However when the m-f transsexual made an official complaint to the HRC about OLO’s refusal to publish his advertisement the HRC (eventually} made a decision not to make a decision regarding the complaint. The issue was extremely stressful for the OLO Collective and caused divisions among Canterbury lesbians. Sadly some cancelled their subscriptions to OLO. The OLO Collective was united in its decisions not to publish the advertisement and not to allow the m-f transsexual to join the Collective.